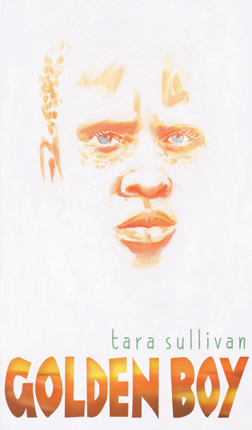

Full Text Reviews: Booklist - 06/01/2013 Born albino in a Tanzanian village, Habo suffers virulent prejudice for his pale skin, blue eyes, and yellow hair, even from his own family. At 13, he runs away to the city of Dar-es-Salaam, where he thinks he will find more acceptance: there are even two albino members of the government there. He finds a home as an apprentice to a blind sculptor who knows Habo is a smart boy with a good heart, and he teaches Habo to carve wood. But Habo is being pursued by a poacher who wants to kill him and sell his body parts on the black market to superstitious buyers in search of luck. Readers will be caught by the contemporary story of prejudice, both unspoken and violent, as tension builds to the climax. Just as moving is the bond the boy forges with his mentor, and the gripping daily events: Habo gets glasses for his weak eyes, discovers the library, and goes to school at last. The appended matter includes a Swahili glossary and suggestions for documentary videos. - Copyright 2013 Booklist. School Library Journal - 07/01/2013 Gr 8 Up—Habo, 13, knows that his albinism makes him a zeruzeru, less than a person. His skin burns easily, and his poor eyesight makes school almost impossible. People shun or mock him. Unable to accept his son's white skin and yellow hair, his father abandoned the family, and they cannot manage their drought-ravaged farm in a small Tanzanian village. Habo and his mother, sister, and brother travel across the Serengeti to seek refuge with his aunt's family in Mwanza. Along the way, they hitch a ride with an ivory poacher, Alasiri, who kills elephants without remorse for the money the tusks bring. In Mwanza, the family learns that one commodity can fetch even higher prices: a zeruzeru. Rich people will pay handsomely for albino body parts, and Alasiri plans to make his fortune. Habo must flee to Dar es Salaam before he is killed. After a harrowing escape, he reaches the city and miraculously encounters a person to whom his appearance makes no difference: a blind woodcarver named Kweli. Slowly Habo develops a sense of self-worth as well as carving skills. When Alasiri brings ivory for Kweli to carve, the boy and old man work with the police to send the hunter to prison. Habo's gripping account propels readers along. His narrative reveals his despair, anger, and bewilderment, but there are humorous moments, too. Although fortuitous encounters and repeated escapes may seem unlikely, the truth underlying the novel is even more unbelievable. In Tanzania, people with albinism have been maimed and killed for their body parts, thought to bring good luck. Readers will be haunted by Habo's voice as he seeks a place of dignity and respect in society. An important and affecting story.—Kathy Piehl, Minnesota State University, Mankato - Copyright 2013 Publishers Weekly, Library Journal and/or School Library Journal used with permission. Bulletin for the Center... - 09/01/2013 To be an albino in certain parts of modern-day Tanzania is a dangerous thing: a relatively new superstition holds that the body parts of albinos, including hair, legs, and skin, bring luck. More dangerous, though, is that the trade in these things brings money, and lots of it, to unscrupulous hunters and wagangas. As an albino, Habo is painfully aware of his difference, which makes him unable to work in the hot sun and to see with clarity, but he is unaware of his danger until his family moves to Mwanza, where the police turn a blind eye to the killing and maiming of albinos. Pursued by a hunter his family met along the way, Habo escapes to Dar es Salaam, where he is taken in and tutored by a blind sculptor whom he tried to rob. Habo hides his albinism from Kweli at first, but as the two form a friendship, he realizes that Kweli is the sort of person who can see beyond superficialities to the person within. In addition to exposing a despicable practice, Habo’s story is an especially well-crafted tale of acceptance and the power of friendship and family in the face of adversity. Sullivan is sensitive to the communitarian values of Tanzanian culture, depicting with admirable subtlety the ways her various characters, good and bad, scared and heroic, live out their relationships to family, belief, cultural tradition, and greed. Kweli’s and Habo’s sculptures are both metaphor and vehicle for Habo’s coming of age; readers will be captivated and inspired by Habo’s story as well as horrified by the practice that endangers his life. Resources for information and activism are included, as is a glossary of the Kiswahili terms used in the book. KC - Copyright 2013 The Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. Loading...

|